Weathering Stormy Seas

I just finished assembly in time. A gale was forecast for my area and the wind and sea began to come up again slowly all the next day. By nightfall I decided to lie a-hull again, so I downed sail, removed the wind vane and went below. She rode comfortably so I had supper and turned in. Apart from an occasional slap from a breaking wave it was very peaceful and I slept well.

At 0130 I was awakened to find the boat almost upside down. I found myself looking into a jumble of objects below me —in the cabin roof. My canvas bunk ‘board’ held me, and before I realized what was up (or down) she righted herself. I could still hear the halyards rattling, so I assumed the mast was O.K. I set about clearing up in the cabin. The nasty thing was that it could happen again any moment The only damage below was to the oil lamp shade — chipped, to two eggs —cracked, and to my confidence —shaken. At that moment I decided to run before the next gale. I looked out at my mast. It looked all right but the masthead radar reflector was gone, washed off into the sea.

The ink blotches on my barograph trace showed that the knockdown had occurred at the low point of the pressure drop. The gale had come up relatively quickly and the seas were not more than 10 feet or so. (I found wave height and wind speed very hard to judge, and still do.)

The ink blotches on my barograph trace showed that the knockdown had occurred at the low point of the pressure drop. The gale had come up relatively quickly and the seas were not more than 10 feet or so. (I found wave height and wind speed very hard to judge, and still do.)

The rudder was still attached and undamaged, although the righting impact had resulted in grave internal injuries to the SSG — I should have to steer manually until the seas went down enough to do a rebuild. By 0600 I was underway again — mainly to reduce the rolling motion of lying a-hull with a dying wind.

After steering all day and heaving-to that night I spent the next day replacing the damaged parts of my self-steering units. A big ship came over to see that I was O.K., and as I was in the habit of not wearing clothes I was caught by surprise. By the time I had returned from below with trousers they had established I was O.K. and turned back on course.

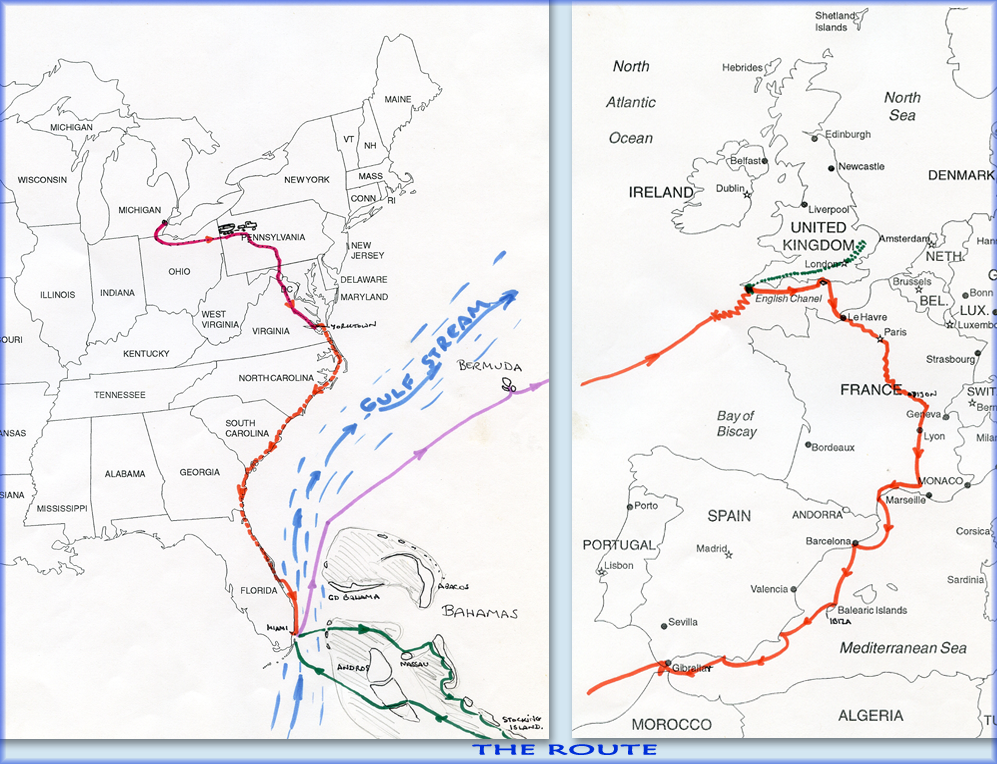

Following this storm I had a period of light and N.E. winds. A large high pressure area which had produced a heat wave in the U.S and later was to do the same in England was passing over me. During one of the occasional thunder showers I collected 6 gallons of rainwater from the mainsail and thus relieved my worries about drinking water. I had been consuming almost a gallon a day in the hot weather rather than the 1/2 gallon allowed for. During this period I passed the 1,000 mile mark and opened a surprise food parcel. I blessed the donors and ate luxuriously for a few days.

After three days of head-winds forcing me to go SE. towards the Azores (which I hoped not to visit) a S.W. wind came up and slowly got stronger and stronger. To make some distance in the building seas I steered manually from midday one day to the evening of the following day. By this time the wind was up to gale force and I had to keep going —this time under reefed main alone.

I must have headed right into the center of a depression as I spent most of the night surfing along with an electrical storm close off the port beam. It was too exciting for me to feel tired, although I felt as though I was never going to leave the storm behind. This was the first time I had used the safety harness, and it was just as well, as it saved me from being washed headfirst over the cockpit side in one large well-aimed wave.

At first light I found myself under a large black cloud-mass that looked like the textbook picture of a cold front. Lumpy seas, rain and gusting winds seemed to follow in whichever direction I turned. Finally when I got out from under the cloud, only light winds and lumpy seas remained, and I was able to heave to and sleep. This was the 6th September, and I had not taken a sight since 3rd September. I was trying to head as far north as possible to avoid the Azores. My sight on the 7th showed that I had blown around the top of the Azores passing within 100 miles of the nearest island. I had covered 400 miles in four days, which had included probably 20 hours lying hove to or moving slowly. Storms do get the miles covered —only 1300 miles to England.

For the next three days I seemed to run continually into the back of my depression, which was also making slow progress towards England. Finally it left me behind and I had a few days traveling fast and comfortably on self-steering.

By 11th September I was less than 1,000 miles to Falmouth, and opened my second surprise parcel. Four kinds of bread in tins —heaven after a diet of crackers. I had noticed in myself an occasional preoccupation with the thought of food, even though I ate pretty well all the way over. Having met a couple of pretty girls in Bermuda, my colorful thoughts lasted a couple of days but those mild longings turned to food for the rest of the trip! A psychologist could probably explain the hierarchy of desire – since I was safe, food came next!

I have memories only of seeing a lot of foam below me to leeward as we rolled over to port, and then I was breathing water.

For the next week I seemed to get in and out of depressions and fronts predominantly with N.W. winds, forcing me to stay almost close-hauled —good for self-steering but giving a wet and bumpy ride. I tended to stay in the cabin reading, eating and sleeping in this sort of weather, and became reluctant to get oilskins on and get out and do things.

By September 17th I was about 350 miles from Falmouth and right in the path of a gale according to the E.E.C. Shipping forecast. Last.one, I thought, get through this and I am home and dry (an expression that I now understand a bit more). I hoped the gale would be well over by the time I reached the Banks where the Atlantic shallows down to the English Channel, as I knew the seas would be short and steep there.

By 2300 the gale was well on me and I steered all night using only the jib. By first light the big gusts were less frequent, and I began to congratulate myself that I would be O.K. A big sea was running, with waves breaking from behind and from my starboard quarter. In my mood of relief and relaxation one of the starboarders broached me around. Nothing untoward happened, and I kept going, thinking to myself that as the wind dropped I needed more sail up to maintain speed and steerage way. I was still doing 4-5 knots, but the waves were catching me too easily.

Suddenly a big wave broke from my starboard quarter. I have memories only of seeing a lot of foam below me to leeward as we rolled over to port, and then I was breathing water. We rolled right over, and before I was aware of what had happened the boat was upright and I was still sitting strapped into the cockpit (wet). The mast had gone —a piece lay on the deck with the boom and the rest was in the water. Alter a good curse, mostly aimed at my own carelessness, I looked into the closed cabin. It was a shambles, but at least a dry shambles, and that was reassuring.

(Con’t on Page 6)

Recent Comments