Some insights and advice…

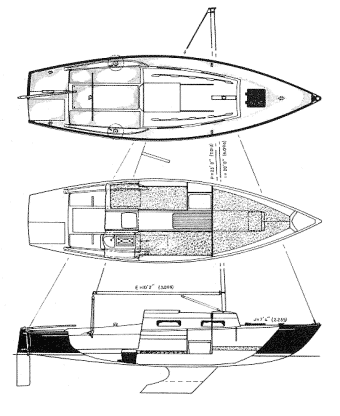

Most of the modifications I had made to the boat had worked well. The canvas covers over the fore, main and lazarette hatches had supplemented the Shark’s minimal sealing. The bridge deck/dinghy locker had reduced the water capacity and weight of a flooded cockpit, kept water out of the cabin and gave me more surface to sit or lie on. The lid of the locker was tied down with small line and I had a sharp knife secured right by so that I could get the dinghy out of the locker fast. I also had a manually operated CO2 bottle pre-fastened to the dinghy with water, food fishing gear and ex-government solar still packed in too.

- The short-wave receiver gave me time signals for navigation, weather reports for coastal US, telling me what was coming my way, and company from the BBC and US short wave programming. Reception was greatly enhanced with the insulated back-stay antenna. I was lucky that hurricanes that year kept going ashore in Belize rather than curving up into the N. Atlantic. The balanced rudder did put more load on its fittings but I think made self-steering much more steady. My thoughts about steering fittings now are that one should be able to lift the boat by the rudder, at the very least!

- The diet of canned food worked well, although I was able to keep potatoes and onions bought in Bermuda for a couple of weeks. I always drank or cooked with the liquid from the can. Store-bought eggs from Florida (seven dozen) were rubbed in Vaseline and repacked in their cartons. They lasted all the way to England with no trouble in spite of many 70-80º days. I did take a multi-vitamin every day for good luck. I mentioned using crackers instead of bread which worked fine (remember hard tack on old sailing vessels!) but I still longed for bread. I had canned butter.

Store-bought eggs from Florida (seven dozen) were rubbed in Vaseline and repacked in their cartons. They lasted all the way to England with no trouble in spite of many 70-80º days.

- When sailing under almost any condition my Sea-Swing gimballed stove, with kerosene pressure stove hung beneath, attached to the main cabin starboard bulkhead, worked well. A gimballed kerosene wick lantern was on the port bulkhead. I had a through-hull Ballhed toilet in standard 1968 Shark position and a through-hull sea water faucet actuated by a foot pump by the cabin floor (not used right after the Ballhed!).

- I carried simple hand tools for metal and wood, plenty of Shark-sized stainless steel hardware, Nicopress tool and fittings good for temporary forestays, For radar visibility I started with a homemade foil lined wooden inside-corner style reflector mounted on top of the mast. When that got washed away I used a tupperware container stuffed with crumpled aluminum foil hoisted into the rigging. For night sailing, I used a kerosene anchor light, with prismatic lens, also hoisted into the rigging, in the slender hope that others might be looking out! More important, I kept away from known shipping lanes and when I had to cross them, I kept a watch of sorts.

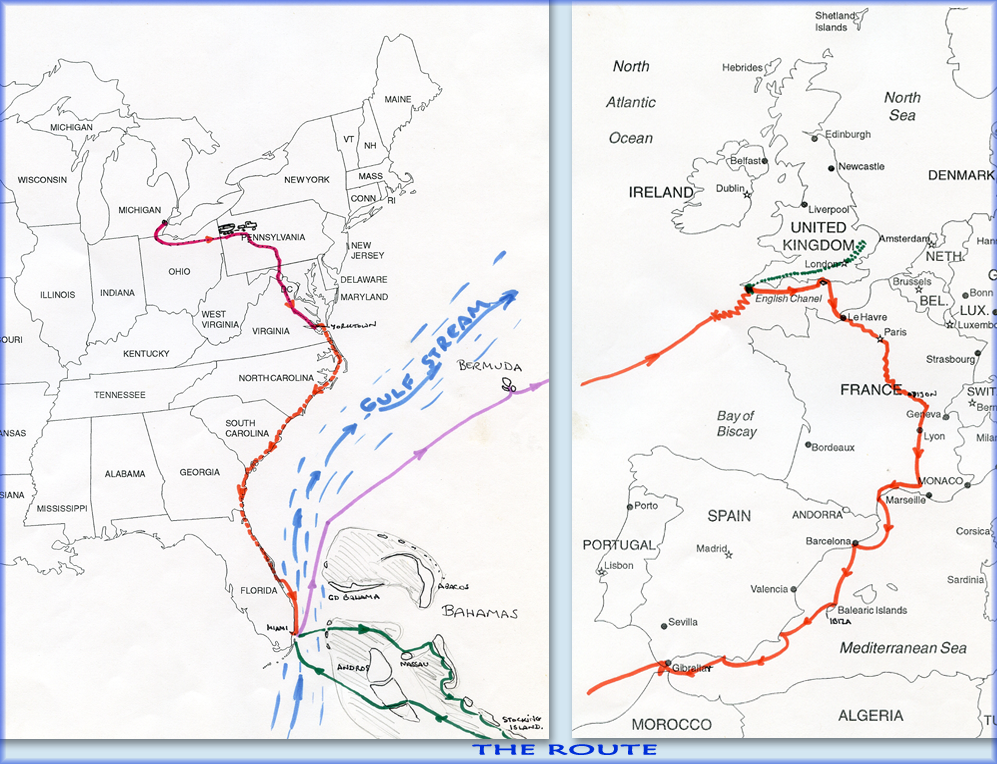

- Traveling well before the advent of GPS, I navigated by sextant, nautical almanac and tables, and seemed to hit landfalls as expected. (Hit is probably not a good word to use with landfalls).

Traveling well before the advent of GPS, I navigated by sextant, nautical almanac and tables.

- I rarely wore my life-harness on deck but relied on ‘one hand for the boat’ and keeping my center of gravity well over the boat when scrambling forward. The thought of seeing the boat sailing away from me under self-steering was enough to make me hold on tight at all times. On the ocean, waves may be high but of long wavelength so a small boat seems to just rise and fall gently with a good view at the top and none at the bottom. Breaking or curling waves in high winds are another matter and when the breaking part is more than 3 feet deep (the approximate draft of a Shark), a small boat can get thrown sideways and trip up, as I did.

- I found that I usually sailed with the main reefed and the working jib. The stouter mast that Hinterhoeller advised, failed on the roll-over partly because the forestay fitting pulled out of the mast. I had only the working jib up.

- Next time I go to sea, I shall have a parachute drogue of large diameter that will enable me to ‘moor’ the boat bow to wind and take all waves more or less on the bow, particularly important for the small boat. This has a secondary advantage for the single-hander. By staying in one place, the storm passes by quickly and one can get some rest. If one runs with a storm, one stays in it much longer, and has to stay at the helm and gets tired.

- If there is one lesson I learned from reading many books on long-distance short-handed cruising, it is of the dangers of becoming tired. When one is tired, one makes mistakes. I took every opportunity for sleep, even in good weather, so that I was prepared for bad.[beautifulquote align=”right” cite=””]If you have a Shark, you can go anywhere. If you prepare well and use some common (sea) sense, it will not be the Shark that lets you down.[/beautifulquote]

The Shark is a tough little boat and is very well made. With a reduction in size of the large cockpit and minor waterproofing it can take a lot of weather. For open ocean tracking, a skeg before the rudder would be ideal and if going in a Shark again, I would add one. An alternative would be to fix the regular Shark rudder and steer using a wind-vane self-steerer that provided an auxiliary rudder, so the Shark rudder acted as the skeg. On the ocean one stays on one course for days at a time so nimble steering is not needed. A separate skeg would take a lot of the load off the rudder supports.

If you have a Shark, you can go anywhere. If you prepare well and use some common (sea) sense, it will not be the Shark that lets you down.

Recent Comments